The summer of 1979, I did what I did every summer, I worked on a road crew in Oregon, mostly carving roads out of alfalfa fields, or hillsides, or mountain forests.

Unlike my other summers, at the end of August, 1979, I packed a suitcase and flew back east to Wesleyan University, which was a fancy liberal arts college in Connecticut.

There, I met a lot of smart and capable kids, mostly from wealthy families. Some of the kids were not wealthy, but had interesting backgrounds or unique talents. Thanks to my road crew job, I was one of the “interesting backgrounds” people.

*

*

School started and I had the usual difficulties getting up to speed in this new and rarefied environment. Almost everything appeared slightly alien to me, including a strange-looking newspaper called The Village Voice, which I came across in the Social Sciences lounge below my dorm.

I knew immediately this publication was from New York City. I could tell because the print was so small. And there was so much of it. Each page was a sea of grey. The actual paper stock felt gritty and rough to the touch.

I tried to read one of the articles. The sentences were long. There were a lot of big words and academic jargon. They referenced political controversies and public figures I’d never heard of. I couldn’t follow any of it.

I imagined the people who engaged with such a publication were professors, intellectuals, people who traveled the world. I could picture these people in book shelved offices, wearing thick European sweaters, stroking their beards while they argued socialism vs. communism.

I could sense that this paper was full of opinions. And ideas. And egos. But it might as well have been in a foreign language. I remember thinking: This is something I will need to know about in the future . . . but I don’t need to know about now.

And so I closed that copy of The Village Voice and continued with my life as a clueless college freshman.

*

*

I didn’t often see The Village Voice at Wesleyan. But I did read the Wesleyan Argus, which was the student newspaper.

I quickly saw that The Argus existed mostly to publish never-ending battles of competing leftist ideas: Stop the Nukes, Save the Whales, End Apartheid: almost everyone was on the same side (the Left), and yet the student journalists and Letters-to-the-Editor commentators still found ways to argue and fight and split hairs.

Despite the predictability of these arguments, I continued to read The Argus. It was the school paper. And this was my school.

And anyway, it was kind of fascinating. What kind of people went around and around in these circular arguments? What were they trying to prove?

*

*

It wasn’t until I dropped out of Wesleyan and moved to New Haven, CT, that I began to see and read The Village Voice with regularity. Because of Yale University and the Metro North Commuter line, New Haven had a much stronger connection to New York City. The Village Voice was commonly found in cafes and pizza joints.

It still seemed beyond me in terms of the complexity of the writing. Often, there’d be an article about something I was curious about: A new movie or the latest Gang of Four album. But within a paragraph or two, it was obvious I was in for a long slog through dense and sometimes incomprehensible prose. Usually, I gave up. But occasionally I’d force my way through to the end, only to remain baffled as to what conclusion the writer had come to.

*

However, The Voice was still from New York City which was the center of the cultural universe. So I felt a certain obligation to flip through its pages every week. And occasionally an article would shock me by being clear and straightforward. During those rare moments The Village Voice was a transcendent reading experience.

Also, as a physical object, The Voice was extremely cool. It had great design, great B&W photos, outrageous headlines. Its subterranean grittiness whet your appetite for the brash, in-your-face, excitement of the Big City.

*

After New Haven, I moved to New York and enrolled at New York University. As an older student, I didn’t want to live in a dorm. I thought I should rent/share an apartment, which was a bad idea. But I didn’t know that then.

To find a New York apartment—I was told—I needed to go to a news-stand late on Tuesday night and when the bundles of Wednesday’s Village Voice arrived, rip one open and check the classifieds for roommates wanted.

I actually did this. Not ripping open the bundle, but getting The Voice at 6:00 am on Wednesday and then frantically running around the East Village to see a few tiny rooms, which a hundred other people were also looking at.

So that didn’t work. I ended up in a dorm instead. Which was just as well.

*

*

Once I was settled in my dorm, and had figured out my classes, I commenced a period of total immersion into The Village Voice.

I didn’t know anyone at NYU, not at first. So to learn what was going on in the city, what bands were playing at Danceteria, what people were talking about, I began by picking up The Voice every Wednesday.

It took time to get used to an environment where rock music was not 95% of the cultural life of young people, which was the case in most American cities.

In New York there was art. And art galleries. Young people actually went to them. There were art parties. With super cute girls!

There were interesting bookstores. And books for sale on the sidewalk. And places you could go see famous authors do readings and give talks. Like every week!

There were underground movie theaters. And special movie screenings. Movies were taken extremely seriously. In New York they called them “films”.

Sam Shepard—a guy who wrote theater plays (???)—was considered as important a cultural figure in New York City as, say, Eddie Van Halen was in Cleveland. NYU girls swooned over Sam Shepard.

*

I didn’t even bother going to CBGBs. By 1983, that scene was over anyway. Now I was reading about THE WOOSTER GROUP and THE KITCHEN where all kinds of unimaginable weirdness was taking place. People were doing “performance art”.

And there were still jazz clubs. Like real ones. The Village Vanguard was just down the street from my dorm. I walked by it all the time. Sometimes there’d be famous musicians standing around outside. Not that I knew who they were. But I could tell they were famous.

*

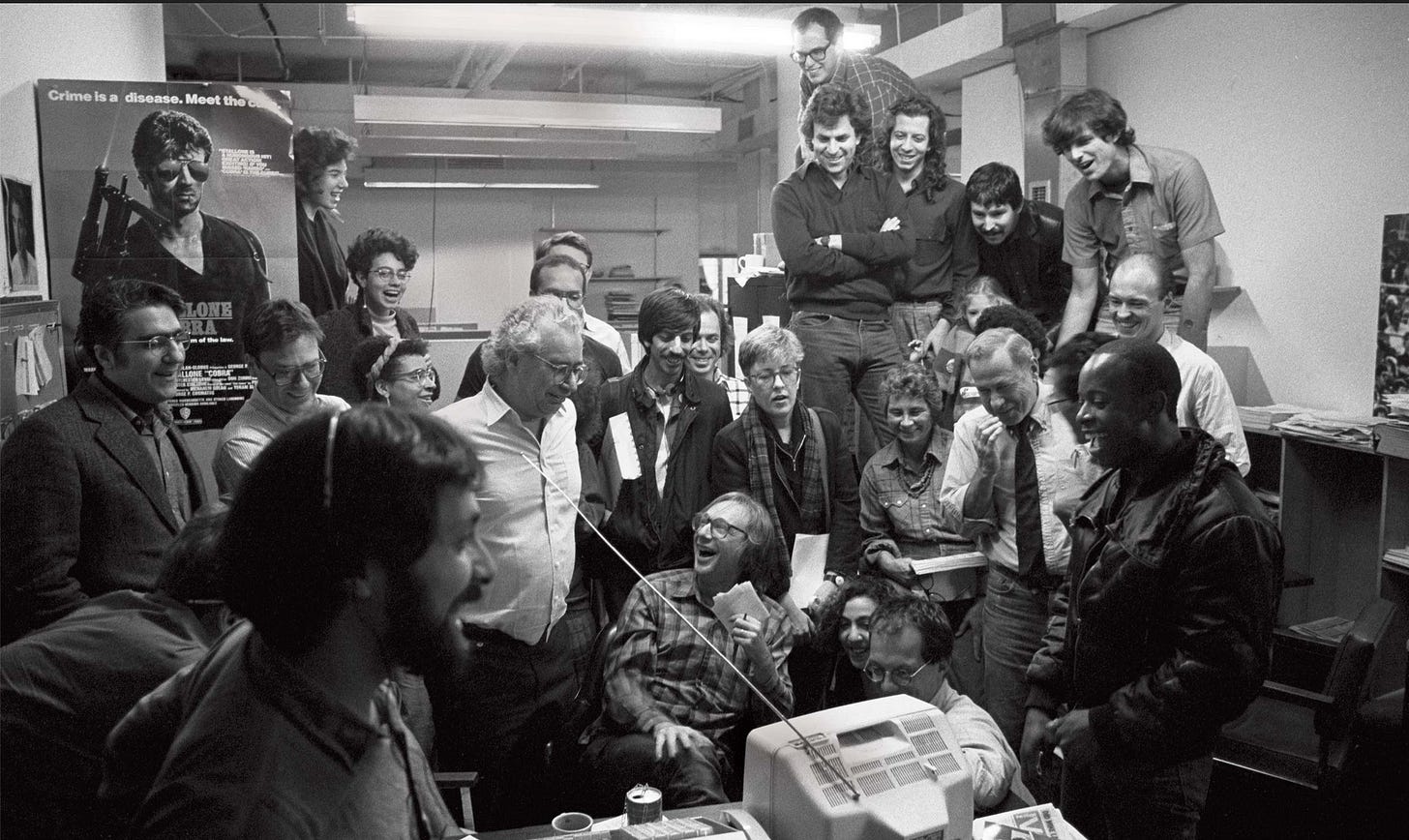

Covering all this stuff was The Village Voice. Which seemed to contain its own unique subculture. Who were these writers, who knew about all this stuff?

They were older than me, obviously. And smarter. And better educated. And they knew a lot of stuff I didn’t know. They were definitely more theoretical and philosophical and ideological than I was.

Nat Hentoff was the star of the paper. His articles were announced with great fanfare on the cover. “Nat Hentoff on The New Bohemia”. Or “Nat Hentoff: The Death and Resurrection of Miles Davis”.

Hentoff’s articles were always right at the front when you opened the paper. I pictured him as a hip, 40-ish college professor type. A cool radical activist.

But reading his articles? I tried to read them. Sometimes the headlines would draw me in. But I don’t think I ever finished a single one.

It was mostly a generational thing. He was a 60s guy. He thought like that. He wrote like that. To him Bob Dylan was the most important artist walking the earth.

And all the politics. That was the problem with the all articles in The Voice. The endless politics. And the tone the writers would adopt when they discussed politics. The pomposity. The self righteousness. It was awful.

I was an E. B. White guy. I believed in clarity, simplicity, humility. The Voice was the polar opposite.

*

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to TRAVELS TO DISTANT CITIES to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.